São Cucufate Roman villa - Part 1

Located in the tranquil countryside c.4km to the west of Vidigueira (central Alentejo), the archaeological site of São Cucufate is one of Portugal’s best known Roman villas, boasting well-preserved structural remains and a long history of occupation.

This article is divided in two parts. This first part presents an introduction and covers the following topics:

- Occupation, later use and abandonment

- Local context and surrounding landscape

The second part will present concluding comments and information related to Preservation and commentary, in particular:

- The west wing: exterior

- Cisterns and water management;

- The west wing: interior

- The bath-house

- The Pars Rustica

- Mausoleum/temple

Foreword

This article is offered as an introductory overview of São Cucufate to support the Augmented Reality in Cultural Heritage project research by Ms Anabela Marto. It is not intended to provide an authoritative, comprehensive discussion of the site as a whole, but rather, to focus on a select range of the surviving architectural remains and related material: in all instances readers are directed to the list of publications that are provided, each of which has been authored by scholars who have either worked directly with the material or presented their own interpretations based on the excavated remains. Any mistakes or errors are my own and do not represent the views of the authors listed after this discussion: many of the specific details concerning occupation phases (Roman and post-Roman) and references to specific archaeological material can be found in these works. Much of the commentary below is based on these sources in addition to first-hand knowledge from site visits in 2017 and 2018, together with doctoral research I completed at the University of Nottingham (2004-2007).

Introduction

Located in the tranquil countryside c.4km to the west of Vidigueira (central Alentejo), the archaeological site of São Cucufate is one of Portugal’s best known Roman villas, boasting well-preserved structural remains and a long history of occupation.

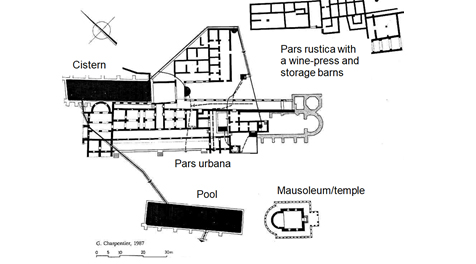

Extensive archaeological research, including that by Alarcão, Étienne and Mayet, has revealed the full extent of the site, with the remains distributed over an area of approximately 130 by 90 metres: these include the central parts of the villa with a dining room (triclinium) and a bath-house within the pars urbana, a series of agricultural buildings, two large cisterns and a freestanding structure thought to be a mausoleum (figure 1). The site itself is positioned on a gentle south-east facing slope, with the surrounding landscape characterised by slight hills and shallow valleys, with many of the fields today used for the cultivation of the vine.

Figure 1. Site plan of São Cufucate (adapted). Source: Alarcão 1998.

The name of the villa arose through the association with São Cucufate, who came to be venerated here in the Middle Ages. Today, the site is well-known for its distinct standing remains which, in some sections, make it possible to explore a series of internal rooms and corridors on the ground floor, complete with ceilings and supporting arches, all of which demonstrate well Roman masonry construction techniques (figure 2). Being able to experience a Roman villa this way is relatively unusual and can be explained, to an extent, by the later installation of a Christian chapel which ultimately saw parts of the western wing preserved, while others fell in to ruin.

Figure 2. Standing remains from the west wing of the pars urbana at São Cucufate. Photo by A.Souter.

We are also fortunate to know something about the agricultural aspects of the site based on excavations in the eastern sector, typically referred to as the pars rustica. Here, a wine-press facility has been discovered, in addition to associated storage rooms and a nearby granary. Although the structural remains from this part of the villa are reduced to their foundations, excavations have recovered agricultural tools, coins and pottery, examples of which are on display in the small museum at Vidigueira. Some of the material includes rare examples of iron lopping tools used for harvesting grape vines (falx vinitoriae), loom weights for textiles, and also a large collection of amphorae used for fish-products, olive oil, and possibly wine. These discoveries therefore provide important insights concerning daily life and agricultural practices on the estate.

Occupation, later use and abandonment

Initiating in the middle of the 1st century AD, the site first began as relatively small and basic farmstead, with a series of rooms loosely arranged around a courtyard, with some indications for the production and storage of wine. Occupation continued into the 2nd century, during which the early settlement was subject to restructuring and expansion, with new buildings added to the west and south, which then ultimately gave rise to further developments in the 4th century AD: the standing remains we see today, including the baths, belong to the later phases of the site’s Roman history and clearly demonstrate the construction of what might be described as a fortified country residence. Of further significance is that the owners maintained the courtyard area from the earlier farmstead and invested in two wine-presses with associated storage rooms, thereby indicating significant levels of agricultural activity, with the produce most likely intended for sale in local markets and on-site consumption. Following the collapse of power in the Roman west by the early 5th century AD, the villa was largely abandoned, thereby reflecting the economic and social ramifications of the deteriorating Empire, after which much of Iberia was subject to Visigothic control. Nevertheless, the conversion into a Christian chapel of what had previously been a granary within the western wing ultimately served to preserve part of the site: first installed in the 6th century AD, only by the early 18th century did the chapel finally fall out of use, after which the site was completely abandoned, to then be rediscovered and investigated by archaeologists in the 1970s and 80s.

Local context and surrounding landscape

Before specific aspects of the villa are considered, it is important to briefly consider the wider context within the provincial landscape; afterall, for any Roman rural site to flourish, while the quality of local agricultural land and type of climate were of fundamental importance, it was equally crucial to be integrated within some form of local infrastructure, with potential access to markets for the sale of produce and the import of goods and resources. In this case, the villa was located deep in the countryside, albeit in close proximity to a road. The nearest urban settlement was the Roman colony of Pax Iulia (Beja), located approximately 23km to the south, with Roman Ebora (Evora), some 40km to the north. Although still a considerable distance, we know that the owners had access to local markets and were integrated within a monetary economy, as demonstrated through numerous coins and the import of significant quantities of table-wares (sigillata) and amphorae. Concerning the latter, many examples of containers used for fish-products are known, typically imported from western coastal areas some 85km away, largely from the Sado Estuary region, with further examples known from the Algarve some 130km to the south, and even further, with a small quantity of olive oil amphorae from the neighbouring province of Baetica in southern Spain. The presence of such material at the villa most likely reflects the commercial movement of goods circulating in local markets, perhaps en route to the urban settlements. On a more local level, field survey has revealed that the surrounding landscape was populated by several other contemporary villas and smaller farmsteads. As such, the site was well-placed within the provincial infrastructure, with access to local consumer markets. The impression therefore is of a rural site that was well-placed and integrated, rather than isolated: furthermore, the long period of occupation throughout the Roman era demonstrates the ability of the owners to sustain and invest in the site for many generations.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful for the opportunity to support Anabela’s research project and to highlight some of the archaeological remains at São Cucufate, especially for those readers who are generally unfamiliar with the site. I am also grateful for Professor J-P. Brun’s permission to use the plan of the wine-press facility (figure 21). Only in the case of Professor J.Alarcão’s plan of the site (figure 1) has it not been possible to make contact for authorisation. All of the other images are my own and were taken during recent visits; should you wish to use these, all I request is a brief acknowledgement.

Further reading

Alarcão, J. 1998. S.Cucufate. Roteiros da Arqueologia Portuguesa. Portugal: Instituto Português Do Património Arquitectónico (IPPAR).

Alarcão, J. 2000. São Cucufate ruins. Itinerários Arqueológicos do Alentejo e Algarve. Portugal: Instituto Português Do Património Arquitectónico (IPPAR).

Alarcão, J., R.Étienne, and F.Mayet (eds). 1990. Les villas romaines de São Cucufate (Portugal). Paris: De Boccard.

Brun, J.-P. 2004. Archéologie du vin et de l’huile dans l’Empire romain. Paris: Errance.

Étienne, R., and F.Mayet (eds). 1997. Itinéraires lusitaniens. Trente années de collaboration archéologique luso-française. Actes de la réunion tenue à Bordeaux les 7 et 8 avril, à l’occasion du trentième anniversaire de la Mission Archéologique Française au Portugal. Paris: Diffusion E. De Boccard.

Gorges, J.-G. 1979. Les Villas Hispano-Romaines. Inventaire et Problématique archéologiques. Talence: Université de Bordeaux III; Paris: E. de Boccard.

Mayet, F., and A.Schmitt. 1997. “Les amphores de São Cucufate (Beja).” In Étienne and Mayet (1997), p.71-109.

Pinto, I.V. 2003. A cerâmica comum das villae romanas de São Cucufate (Beja). Lisbon: Universidade Lusíada.

SensiMAR

SensiMAR