São Cucufate Roman villa - Part 2: Preservation and commentary

This second part presents concluding comments and information related to Preservation and commentary.

The west wing: exterior

Figure 3 provides a general view of the south-side of the west wing, dating to the 4th century AD, by which time the villa is sometimes referred to as “palatial” given the extent of the remains. In the centre we see a long raised platform with three separate flights of steps (although that on the right is hidden behind the tree). Behind this is a long wall punctuated by square openings and a central doorway which led to a series of internal storage rooms. The wall belongs to an internal corridor, as demonstrated at the far left end in the form of brick arch: this would have run the full length of the wall, supporting a long barrel-vaulted ceiling, traces of which are preserved within the surviving masonry.

Figure 1. Standing remains from the west wing. Photo by A.Souter.

Figure 1 provides a general view of the south-side of the west wing, dating to the 4th century AD, by which time the villa is sometimes referred to as “palatial” given the extent of the remains. In the centre we see a long raised platform with three separate flights of steps (although that on the right is hidden behind the tree). Behind this is a long wall punctuated by square openings and a central doorway which led to a series of internal storage rooms. The wall belongs to an internal corridor, as demonstrated at the far left end in the form of brick arch: this would have run the full length of the wall, supporting a long barrel-vaulted ceiling, traces of which are preserved within the surviving masonry.

At either end of the raised terrace are two large arched niches. Both these and the walls are made from well-constructed masonry, with distinct alternating bands of flat bricks (tegulae) and stone-faced concrete (figure 2).

Figure 2. Detail of one of the tall vaulted niches on the south façade of the villa. Photo by A.Souter.

The thickness and strength of these was most likely to support another level up above, but unfortunately this hasn’t survived. The same technique was used for the nearby mausoleum, thereby placing the construction of these in the same era, in the 4th century AD. As with other parts of the building, traces of white stucco survive at the top, within the curve of the arch. This was most likely added to protect the masonry and prevent dampness penetrating the walls; given that other parts of the exterior also feature the same rendering, this would have meant that, from the outside, the building would have had a white-washed appearance, screening the distinct stone-work that is otherwise exposed today. Whether or not the surviving plaster was added in the Medieval or Roman era isn’t clear, but, as a technique, the application of stucco to the exterior of buildings was a relatively common Roman practice.

Reconstruction drawings in the publications by Alarcão et al suggest the presence of further rooms on the first floor, complete with a long balcony positioned above the full-length of the central terrace. Therefore, in addition to the imposing remains that still stand today, the presence of a second storey would have made this an even grander structure, reflecting the financial means of the owners to invest in an extensive building of well-constructed masonry. Despite the disappearance of the upper level, the installation of a modern platform provides visitors with fantastic views of the site and the surrounding landscape (figures 3 and 4). While these provide us with a good impression of the type of landscape here, views such as these were presumably intentional, enabling the owners to monitor the surrounding estate.

Figure 3. View of the countryside, looking south-east from the villa. In the foreground are remains from one of two cisterns known at the site. Photo by A.Souter.

Figure 4. View of the countryside, looking north. Photo by A.Souter.

Figure 5 provides a view of part of the interior of the central wing of the 4th century villa, complete with a huge section of collapsed roof on the left, and a doorway (centre right) which leads to a series of storage rooms and later chapel. Modern scaffolding has been installed within some of the vaulted sections, together with semi-circular wooden supports. These demonstrate well the Roman vault construction technique, which involved the installation of a wooden framework on which the series of tegulae were placed and set in concrete. Just to the right of this area are remains from the dining room (triclinium), immediately adjacent to a large cistern on the north-eastern side of the west wing.

Figure 5. View of the central part of the villa, forming part of the west wing. Located to the right is a large cistern. Photo by A.Souter.

Cisterns and water management

Crucial to the daily life of the villa was access to water. Walking around the site, visitors inevitably encounter two large basins, variously referred to as pools or cisterns. One of these is located down slope in front of the western wing; measuring approximately 40m by 10m length, with an access ramp in the south-east corner (see figure 6, although note that the ramp is obscured from view).

Figure 6. Detail of one of the water channels that supplied water from the north cistern. Photo by A.Souter.

It is known that this basin was linked to another located uphill to the north via a series of stone-lined channels, examples of which can still be seen today (figure 9). This was clearly a significant feature capable of holding a large volume of water, but its exact purpose isn’t clear. The installation of the ramp would indicate the need for access, but for what purpose; to enable cleaning of the interior? Or was this feature used as an open-air natatio (swimming pool) in the manner of a Roman bath-house? Given the general agricultural nature of the site, it was more perhaps more likely to have served a practical purpose, possibly for irrigating crops nearby.

Located on the north side of the western wing is another rectangular cistern, of a similar size to that located downhill to the south; in this case however, the walls survive to a greater height and measure at least 2m, with a water-proof lining known as opus signinum (figures 7 and 8).

Figure 7. View of the large cistern on the north side of the villa. Photo by A.Souter.

Figure 8. Detail of the water-proof lining applied to the interior of the north cistern. Photo by A.Souter.

Investigations indicate a small inlet channel at the north-east corner which may have formed part of a small-scale aqueduct, which itself was perhaps supplied by a local spring a short distance from the villa; where this might have been is not yet clear. Furthermore, was the tank covered over, or left open to the elements, benefiting from any rainfall? Combined with the other similar tank to the south, these features demonstrate that the storage and management of water was of much significance for the owners, especially given the long, hot summers that prevail in central Portugal. We know that other Roman villas in the province took similar significant measures to control and manage water supply: one such example is that of Pisões villa near to Beja (Roman Pax Iulia) where the owners constructed a dam to supply the estate.

The west wing: interior

Preserved within the centre of the villa are a series of internal rooms running the full length of the west wing, with strong, solid walls and brick-work arches (figures 9 and 10).

Figure 9. Internal view of the vaulted storage rooms, showing Roman masonry and arch construction techniques. Note also the presence of the plaster work. Photo by A.Souter.

Figure 10. Detail of one of the internal brick-work arches. These demonstrate the use of flat bricks known as tegulae. The construction of this type of arch was achieved by using a semi-circular wooden frame supported on scaffolding, upon which series of tegulae were arranged and set in concrete. Photo by A.Souter.

Exploring this part of the site today, it is clear that the thick walls provide a relatively dark and cool interior, even when outside the temperatures exceed 25 degrees Celsius. Rather than providing living quarters (which may have been located on the upper floor), investigations here established that these rooms were most likely used for the storage of agricultural produce: the discovery of numerous ceramic jars (dolia) throughout the interior suggest that they were used for the storage of wine produced at the nearby press, with some of the other rooms serving as granaries. As with parts of the exterior, traces of plaster work can still be seen, most likely to prevent dampness penetrating the walls and causing structural damage, in addition to potentially ruining any agricultural produce (especially cereals).

One of the reasons parts of the villa stand today is due to its later conversion into a chapel, remains of which can be seen in the western wing; features include a simple stone font and a small pulpit and an altar, together with painted frescoes on the walls and ceiling (figures 11 and 12).

Figure 9. View of the small pulpit, font, and painted frescos. Photo by A.Souter.

Figure 10. View of the 17th century frescos by José de Escover and simple stone altar. Photo by A.Souter.

The first chapel was installed in the late 6th century AD, during which it belonged to the Order of Saint Bentos. Following a long period of abandonment during the Moorish occupation of central and southern Iberia, which initiated in the 7th century AD, from the middle of the 13th century the chapel saw a new phase of use following the Christian Reconquista: at the request of King Alfonso 3rd, a second monastery was established, venerating São Cucufate, after which the villa is named.

The bath-house

Complementing the remains from the western sector of the site, other features of interest include a bath-house (figure 11), constructed in the 4th century AD but for reasons unknown never finished, as reflected in the apparent lack of décor (neither mosaics or frescoes are known here).

Figure 11. View looking in to the bath-house. Photo by A.Souter.

Within this complex, a small plunge pool can be seen in figure 12, complete with a series of steps to enable access: this would appear to have been a frigidarium with cool, unheated water. Elsewhere, a hot-room (caldarium) was also installed, complete with brick arches and fragments of tiles known as pilae to support a floor up above: hot-air from a nearby furnace would have circulated under the floor, via the nearby arch, which, as shown in figure 13, has been blocked in. The incomplete nature of the baths could possibly reflect sudden financial hardship, prioritisation of other more pressing matters, or possibly a change in site ownership. While this is subject to debate and speculation, the apparent cessation of the bath-house, a feature which would normally be expected at a prosperous, flourishing Roman villa, is surely significant for understanding the changing nature of the site in its later phase.

Figure 12. View of the small cold plunge pool with steps and waterproof lining (opus signinum). Photo by A.Souter.

Figure 13. View of the blocked in archway from the hot room (caldarium). Photo by A.Souter.

The Pars Rustica

Located in the eastern sector of the site, away from the west wing, are remains from the pars rustica. It was here that the earliest farmstead was known, from the 1st century AD, and then maintained throughout the subsequent development of the villa. Although the buildings have now largely disappeared and are only known from fragmentary foundations (thereby dramatically contrasting with the 4th century western sector), archaeological investigations have revealed granaries, warehouses, and two wine-presses. Concerning the latter, two large cylindrical blocks of stone have been left on display in the location in which they were first discovered (figures 14 and 15).

Excavations also discovered a number of grape-seeds found immediately next to the large weights. Botanical remains such as this have rarely been documented at Roman sites within the province, and are therefore archaeologically very significant; combined with the examples of lopping tools (falx vinitoriae), we therefore have good evidence for the production of wine here, as opposed to, for example, olive oil.

Figure 14. Two large cylindrical weights from the wine press facility. Photo by A.Souter.

Figure 15. Top view of one of the counterweights. Photo by A.Souter.

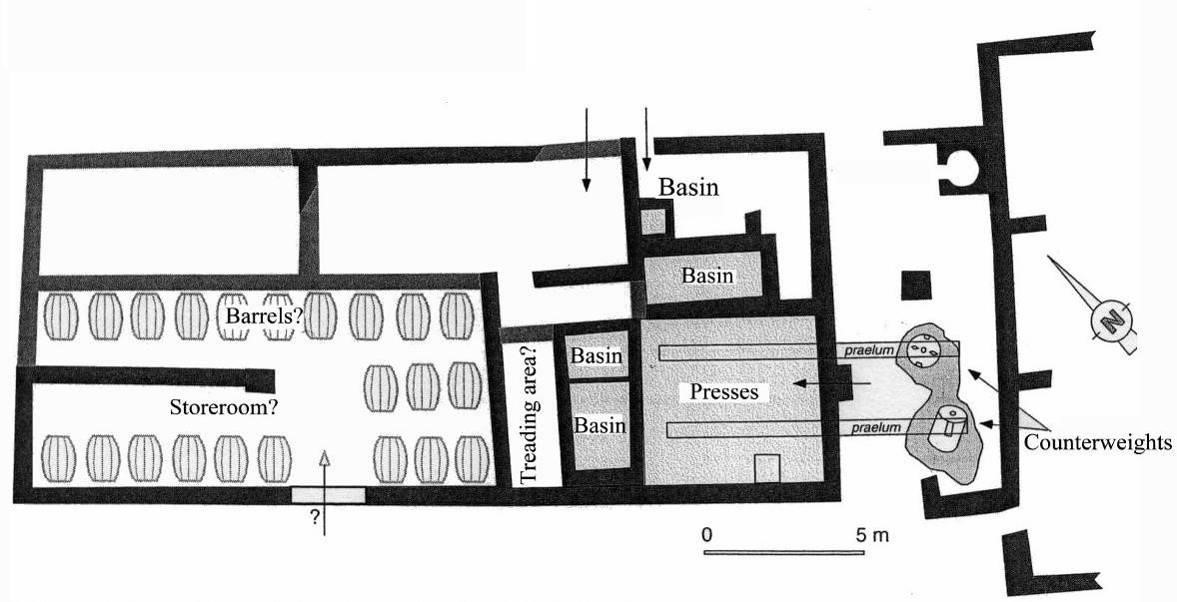

Both the weights feature distinct dove-tail sockets on either side, with a small circular depression in the centre of the upper surface. These features were used to secure a framework (most likely of wood, with metal fittings), attached to a tall vertical wooden screw. This formed part of the press, which included adjacent treading areas and tanks full of grapes. J-P Brun has suggested a theoretical reconstruction of the press facility and associated storage room, as per figure 21.

Figure 16. Plan of the wine-press facility from the pars rustica. Adapted from Brun 2004, 290r.

The juice was then collected and stored for fermentation, perhaps in wooden barrels or dolia¸ examples of which are known from the pars rustica, in addition to the series of rooms within the west wing. The presence of the two presses and associated material therefore indicates the significant role of viticulture for the agricultural life of the villa, with production most likely for marketing purposes, and also on-site consumption. This particular example also demonstrates well that, archaeologically, ancient wine presses typically only survive in the form of stone weights and basins for treading, with any of the wooden apparatus (such as the press beam), long-since perished. Reconstructions such as those by Brun can therefore help us understand how the facility at this villa might have been organised; this is particularly important given that, visiting the pars rustica today, apart from the stone weights there are few visual clues explaining how this part of the site once functioned.

Mausoleum/temple

Finally, located just to the south of the villa some 30m away, is the inner shell of a relatively small structure variously referred to as either a temple or a mausoleum, dating to the 3rd and 4th centuries AD (figure 17).

Figure 17. View of the temple/mausoleum, looking north-west. Image by A.Souter.

Although it doesn’t survive in its entirety, it took the form of a rectangular building with the entrance on the south-east side, with the interior featuring a semi-circular apse and a half-domed ceiling (figure 18).

Figure 18. Detail of the masonry from the mausoleum. Photo by A.Souter.

The walls that we see today belong to the inner structure and demonstrate the use of well-constructed Roman masonry, with alternating levels of tegulae and stone-faced concrete; in other words, the same technique that was used for the western wing of the villa. Mirroring the general shape of the interior are foundation remains (figure 19) which formed part of an external colonnade, thereby lending an air of elegance and sophistication.

Figure 19. Rear view of the temple/mausoleum, complete with foundation remains from the external wall and colonnade. Photo by A.Souter.

Fragments of columnar architecture displayed elsewhere on site indicate that the colonnade may have featured Corinthian style capitals. The discovery of inhumations, with simple grave goods, demonstrates the use of this structure for burials. One of these was found within a marble sarcophagus, thereby indicating a degree of wealth and the burial of an important individual, perhaps the owner of the site or head of the family. The presence of the inhumations here could therefore suggest that this was possibly a family mausoleum, or perhaps a small basilica. While this is open to speculation, it is interesting to note that another similar structure was known at the villa of Milreu (Estoi) located far to the south in the Algarve.

Concluding comments

The impression given by the remains at São Cucufate is that of a large and wealthy rural site, with a long history of occupation and development. With well-made strong walls throughout and amount of space devoted water management and the agricultural life of the estate, the villa clearly flourished and managed to sustain itself for many generations. The presence of a mausoleum which, in its original state was most likely quite ornate, further demonstrates the significant means of the owners to construct a purpose-built structure with associated inhumation burials. Despite this, there are some unusual aspects, namely, the apparent lack of decorative material that would normally be associated with a prosperous Roman villa: there are many examples of villas elsewhere in the province with mosaics, typically displayed in the high-status areas such as the bath-houses and dining rooms: examples include Milreu, Cero da Vila, Pisões, Torre de Palma, and indeed others. The bath-house at São Cucufate would have been a likely place to display such décor, yet this facility was never complete. Alternatively, it may have been that such features were present but later removed or destroyed during the post-Roman eras. Furthermore, many parts of the villa were devoted to agricultural, practical purposes, thereby making the presence of mosaics unlikely; it may have been that the series of rooms on the upper floor featured decoration in the Roman manner, yet this level has entirely disappeared.

It is nevertheless important to focus on what actually survives: as discussed, the remains are extensive, and owe their survival, in part, to the subsequent use of part of the villa in the form of a chapel. Elsewhere, detailed archaeological investigations in the pars rustica have revealed many important aspects concerning agricultural facilities and the production of wine; the two large counterweights indicate intensive levels of production, most likely for marketing and therefore profit.

São Cucufate therefore presents us with an interesting and unique archaeological site in Portugal, unparalleled in terms of style and preservation. The thorough and informative research conducted here by Alarcão et al further demonstrates the insights that can be provided from a rural site that once functioned throughout the period of Roman control. While there are many further details that could be explored, in all cases readers are directed to the list of works provided below.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful for the opportunity to support Anabela’s research project and to highlight some of the archaeological remains at São Cucufate, especially for those readers who are generally unfamiliar with the site. I am also grateful for Professor J-P. Brun’s permission to use the plan of the wine-press facility (figure 21). Only in the case of Professor J.Alarcão’s plan of the site (figure 1) has it not been possible to make contact for authorisation. All of the other images are my own and were taken during recent visits; should you wish to use these, all I request is a brief acknowledgement.

Further reading

Alarcão, J. 1998. S.Cucufate. Roteiros da Arqueologia Portuguesa. Portugal: Instituto Português Do Património Arquitectónico (IPPAR).

Alarcão, J. 2000. São Cucufate ruins. Itinerários Arqueológicos do Alentejo e Algarve. Portugal: Instituto Português Do Património Arquitectónico (IPPAR).

Alarcão, J., R.Étienne, and F.Mayet (eds). 1990. Les villas romaines de São Cucufate (Portugal). Paris: De Boccard.

Brun, J.-P. 2004. Archéologie du vin et de l’huile dans l’Empire romain. Paris: Errance.

Étienne, R., and F.Mayet (eds). 1997. Itinéraires lusitaniens. Trente années de collaboration archéologique luso-française. Actes de la réunion tenue à Bordeaux les 7 et 8 avril, à l’occasion du trentième anniversaire de la Mission Archéologique Française au Portugal. Paris: Diffusion E. De Boccard.

Gorges, J.-G. 1979. Les Villas Hispano-Romaines. Inventaire et Problématique archéologiques. Talence: Université de Bordeaux III; Paris: E. de Boccard.

Mayet, F., and A.Schmitt. 1997. “Les amphores de São Cucufate (Beja).” In Étienne and Mayet (1997), p.71-109.

Pinto, I.V. 2003. A cerâmica comum das villae romanas de São Cucufate (Beja). Lisbon: Universidade Lusíada.

SensiMAR

SensiMAR